|

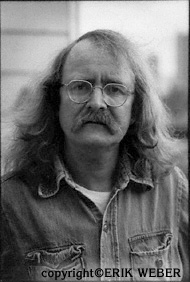

Richard Gary

Brautigan (1935-1984), American novelist, short story writer,

and poet has been called one of the major writers of "New

Fiction" and was considered the literary representative

of the 1960s era known variously as "the hippie generation,"

"the counterculture movement," and "the Age of Aquarius."

He is generally considered to be the "voice" of this time

of tremendous social change, the voice representing the

developing values of the youth of this period.

Brautigan's early

novels were offbeat autobiographical pastorals, and were

widely acclaimed. His later works experimented with different

genres like gothic, science fiction, mystery, and detective,

resisted classification, and were generally considered less

successful by critics.

Save for a campus/underground

cult following, and a growing popularity abroad, Brautigan

all but disappeared from the arena of literary attention

in America in the 1970s when critics began accusing him

of relying too heavily on whimsy and being disconnected

from reality.

This sense of disconnection

was a prevalent theme in his writing. He often used an autobiographical

"I" figure as his narrator, a figure who wandered through

the world as an observer, who seemed "of" the world but

not "in" it, a narrator who observed and reported everything

in an unemotional, matter-of-fact voice. Like the Beat's

"Zen Narrator," none of the events that Brautigan's narrator

witnessed seemed to have any effect on him and the narrator

always moved on to the next observation indifferent, unchanged,

and disconnected.

Disconnection seems

to have come early in Brautigan's life. It's not definitive,

as he refused to discuss his childhood, but what he did

tell helps us understand his later years and offers some

background for understanding and appreciating his writing.

He was born in Tacoma,

Washington, on January 30,1935, the son of Bernard F. and

Mary Lula Brautigan. When he was nine, his mother, according

to Brautigan, abandoned him and his younger sister, Barbara,

age four, in a hotel room in Great Falls, Montana.

It is unclear how

long Brautigan and his sister stayed in Great Falls, but

their mother returned later, reclaimed them, and took them

back to Tacoma. Later they moved to Eugene, Oregon (see Wright)

Brautigan's childhood

wasn't a happy one according to Barbara. "I can never remember

our Mother giving Richard a hug or telling us that she loved

us. We were just there" (see Wright)

There are hints that

Brautigan never knew who his real father was. He apparently

made an effort to find Bernard Brautigan, the man named

on his birth certificate as his father.

After Brautigan's

death the elderly Mr. Brautigan denied that he ever met

his son. According to an October 27, 1984, UPI news story,

"The death of author

Richard Brautigan shocked a Tacoma man who learned for

the first time he was the 49-year-old writer's father.

Bernard Brautigan, 76, a retired laborer, discovered his

relationship to the Tacoma-born writer Friday in a telephone

call from his ex-sister-in-law, Evelyn Fjetland.

"At first he did

not believe the story but he said he called his ex-wife,

whom he has not seen in 50 years. Brautigan was formerly

married to... Mary Lula Folston... who gave birth to Richard

on Jan. 30, 1935.

"Folston... [said]

her ex-husband asked 'if Richard was his son, and I said,

no. I told him I found Richard in the gutter.'

"Bernard Brautigan

said he knew nothing about his famous son... 'I never

read any of his books,' he said. 'When I was called by

Evelyn, she told me about Richard and said she was sorry

about his death. I said, 'Who's Richard?' I don't know

nothing about him. He's got the same last name, but why

would they wait 45 to 50 years to tell me I've got a son?'"

(Anonymous).

Brautigan began writing

in high school, perhaps as a means of expression, or escape.

"He wrote all night," Barbara recalls, "and slept all day.

My folks rode him a lot. They never listened to what he

was writing. They didn't understand his writing was important

to him. I know they asked him to get out of the house several

times" (see

Wright)

In 1955, Brautigan

showed his writing to a girl he had a crush on. She criticized

it and Brautigan was shattered, terrified. He threw a rock

through the police station window, was arrested, and spent

a week in jail. He was then committed to the Oregon State

Hospital and diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic (see

Wright)

Barbara says he received

shock therapy and after he returned from the hospital he

was very quiet and never opened up to her again. A few days

later, Brautigan called to say he was going away forever.

(see

Wright)

"I guess he hated

us," his mother said. "Or maybe he had a disappointed love

affair. Whatever. Richard practically abandoned the family

when he left here. I haven't the slightest idea why" (see

Wright)

Brautigan always

maintained that his formal education consisted only of high

school. In later years, Brautigan said that he spent a great

deal of time as a young man trying to learn how to write

a sentence.

"I love writing

poetry but it's taken time, like a difficult courtship

that leads to a good marriage, for us to get to know each

other. I wrote poetry for seven years to learn how to

write a sentence because I really wanted to write novels

and I couldn't write a novel until I could write a sentence.

I used poetry as a lover but I never made her my old lady.

"One day when I

was twenty-five years old, I looked down and realized

that I could write a sentence... wrote my first novel

Trout Fishing in America and followed it with three

other novels.

"I pretty much

stopped seeing poetry for the next six years until I was

thirty-one or the autumn of 1966. Then I started going

out with poetry again, but this time I knew how to write

a sentence, so everything was different and poetry became

my old lady. God, what a beautiful feeling that was!"

[Meltzer 304].

In 1956, Brautigan

was 21, and living in San Francisco. It was the heyday of

the Beat Generation and San Francisco was full of young

writers and poets like Jack

Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Robert

Creeley, Michael

McClure, Philip

Whalen, Gary

Snyder, and others, all hoping to give America

a new literary voice.

Brautigan was working

at odd jobs and writing poetry but was too shy to read it

in any of the North Beach coffeehouses where the Beats hung

out. Besides, his more humorous (which they thought queer)

and benign view of things was quite out of fashion with

Beat sentiments.

Brautigan published

The Return of the Rivers (a single poem) in 1957,

The Galilee Hitch-Hiker (a single poem) in 1958,

Lay the Marble Tea (a collection of 24 poems) in

1959, and The Octopus Frontier (22 poems) in 1960,

and a novel, A Confederate General from Big Sur in

1964. None were successful.

In 1967, Brautigan

at last found success with his novel, Trout Fishing in

America. Written in 1961, the manuscript had been rejected

by numerous publishers until Four Seasons Foundation of

San Francisco decided to take a chance on it. Critics acclaimed

Trout Fishing in America as "New Fiction" and welcomed

Brautigan to the American literary scene as a fresh new

figure, in the tradition of Mark

Twain and Ernest

Hemingway.

America was looking

for a new literary voice then. The Beats were out of favor

and the rose-tinted, magical, mystical drug experiences,

sexual freedoms, and popular music of the 1960s counter-culture

movement were in. Brautigan certainly recognized, among

America's youth, a dissatisfaction with the absurdities

of the 1960s and a concurrent nostalgic longing for the

past and because of media exposure, quickly became the literary

guru of this changing young America that identified with

his use of imagination and good humor to give zest and humility

to life, his unorthodox use of language, and the original,

playful, eccentric brilliance of his poetry and fiction

which seemed to shatter ordinary notions of experience and

then reconstruct them with whimsy and startling metaphors.

With the publication

of In Watermelon Sugar in 1968, and a renewed interest

in A Confederate General from Big Sur, Brautigan's

reputation as a fiction writer seemed secure. These novels,

like Trout Fishing in America, were told from the

point of view of an "I" narrator who spoke of a new vision

for America, suggesting that through imagination one could

achieve an escape and a salvation from an increasingly mechanized,

urban country.

But while his writing

mourned the betrayal of the American Dream and promoted

the search for a new American Eden, there was also a darker,

more existential philosophy in Brautigan's work. As in Samuel

Beckett's Waiting for Godot, the

characters in Brautigan's A Confederate General from

Big Sur are waiting for someone who will give meaning

to their lives. Brautigan, like Godot, says there is no

one ultimate solution or ending but rather multiple endings,

infinite endings. He "ends" this novel by saying,

"Then there are

more and more endings: the sixth, the 53rd, the 131st,

the 9,435th endings, endings going faster and faster,

more and more endings, faster and faster until this book

is having 186,000 endings per second" [160].

In Watermelon

Sugar ends just as it began: in "deeds that were done

and done again as my life is done in watermelon sugar."

Time does not flow here, it, in the spirit of Kenneth

Patchen's Albion Moonlight, "just is."

Time is told only by the fact that a different color sun

rises every day over the utopian community of... Death.

In this novel Brautigan

seems to outline the communal ethics necessary for the success

of the new "Aquarian-Agrarian" world that was popularly

viewed at the time. In Watermelon Sugar may be considered

a "tract" -- a guide for survival in the post-apocalyptical

world. Brautigan seems to be saying that in order for a

utopian community to be successful, a great deal of emotional

repression and deprivation is necessary. And, that, like

the people of iDeath, one must turn one's back on the surrounding

world and shut all emotions and history away, forever, in

"The Forgotten Works." In Watermelon Sugar is a Surrealistic

aesthetic, an exercise in a world where the I and the not

I, the interior and the exterior, the dream and the waking,

and even silence and speech are possible forms of equally

concurrent reality.

These three novels

seemed to capture the spirit of an extraordinary moment

in American history which advanced the thought that it was

no longer necessary to see things as one had been taught

to see them and what one had learned to call reality was

only one version, and possibly not the best version, of

the surrounding world. These novels seemed to be the first

light of the dawning new age. Counter-culture advocates,

and indeed, for a short time, the critics, loved them.

Brautigan was suddenly

tremendously popular, and in great demand. After years of

handing out his poetry on the streets of Haight-Ashbury,

he was ensconced as the poet-in-residence at the California

Institute of Technology in 1966-1967. He lectured at Harvard,

and articles about him appeared in Time and Life magazine.

Brautigan, the untraveled, uneducated, northwest country-bumpkin

had arrived.

With the publication

of his later novels, critics began to lament that Brautigan

was no longer in a shape that was recognizable to them.

The Abortion: An Historical Romance, 1966 (published

in 1971 and dealing with the extreme narcissism and the

implications of being deeply withdrawn into self) brought

uneven response, as did All Watched Over by Machines

of Loving Grace (collected poetry published in 1967)

and The Pill Versus the Springhill Mine Disaster

(a collection of most of his previous poetry published in

1968). Critics wondered where the vibrant, exuberant, youthful

Brautigan of Trout Fishing in America and In Watermelon

Sugar was. They felt these new Brautigan works were

unstructured ramblings occasionally sparked by whimsy and

wonderful metaphors but wondered if Brautigan could sustain

himself.

Brautigan published

a collection of short stories entitled Revenge of the

Lawn: Stories 1962-1970 in 1971, and it was clear that

he was not going to "continue" in the same vein as his earlier

work, much less "sustain" it. He experimented with different

literary genres: a parody of westerns and gothic horror

films in The Hawkline Monster: A Gothic Western (1974),

a parody of sadomasochistic books like The Story of O

in Willard and His Bowling Trophies: A Perverse Mystery

(1975), a study of the alienation and purposelessness of

being divided from any world of shared experience in Sombrero

Fallout: A Japanese Novel (1976), and a parody of hard-boiled

detective fiction in Dreaming of Babylon: A Private Eye

Novel 1942 (1977). He also published two more books

of poetry, both collections of previous work: Rommel

Drives on Deep into Egypt (1970) and Loading Mercury

with a Pitchfork (1975).

Because of the timing

of his success with Trout Fishing in America, Brautigan

was often called "the hippie novelist," a term that puzzled

him. "I never thought of myself as a [hippie novelist],"

he said in rebuttal, "My writing is just one man's response

to life in the 20th Century" [Bozeman Daily Chronicle 6].

Brautigan's response

to the 20th Century was the casual injection of faintly

surrealistic elements into his fiction. There was a quality.

suppressed but evident, in his early works which promised

much. But he seemed unable to go beyond it, or to develop

it [The Times 12]. The sincerity and the disconnected, elliptical

style of Brautigan's writing that had so charmed critics

and readers in the early years, palled. Critics enjoyed

his Hemingway style, Twain humor, and unique philosophy,

but they generally dismissed Brautigan as a writer who had

peaked early and had nothing new to offer.

Terence Malley, in

his book Richard Brautigan summarized the eventual

critical consensus when he said,

"Brautigan's books

are for the most part directly autobiographical and curiously

elusive. For one thing, it's usually difficult to separate

confession from whimsy... For another, although he draws

heavily on his pre-San Francisco experiences in his writing,

those 'old bygone days' are what he describes as 'years

and years of a different life to which I can never return

nor want to and seems almost to have occurred to another

body somehow vaguely in my shape and recognition...'"

[18-19].

Richard Brautigan

was expelled from the arena of critical literary attention.

As Thomas McGuane,

noted Western author and Brautigan's friend, succinctly

put it: "When the 60s ended, he [Brautigan] was the baby

thrown out with the bath water" [Bozeman Daily Chronicle

6].

Possibly, because

he was disappointed over the lack of positive critical acclaim

he received in the United States, Brautigan allegedly refused

to give lectures or grant interviews from 1972-1980. He

divided his time between California, Montana, and Japan. California

was "home," Montana was a solace, a retreat, and Japan was

a source of acceptance and acclaim not afforded in America.

He had a substantial following in Japan and traveled there

often.

He published another

book of poetry, June 30th, June 30th in 1978, and

another novel, The Tokyo-Montana Express in 1980.

Both were about his experiences in Japan and Montana.

With the publication

of The Tokyo-Montana Express, Brautigan began granting

interviews, giving readings and lectures, and even participating

in "writer in residence" programs, teaching creative writing

once again.

So the Wind Won't

Blow It All Away, Brautigan's last novel, was published

in the summer of 1982. When it was not accepted and acclaimed

by the critics or the reading public he felt misunderstood

and alienated. Accounts from friends say that Brautigan

became depressed and drank heavily.

On October 25, 1984,

Brautigan's body was discovered in his Bolinas, California

home. He apparently had taken his own life some weeks before.

He was 49.

Sources

Anonymous. "Brautigan."

File 260: UPI News-April 1983-May 1987. Dialog Database.

Palo Alto, CA: Dialog Information Service, Inc. Dateline:

Tacoma, WA, October 27, 1984. General news story dealing

with Bernard Brautigan, Richard's father.

Malley, Terence. Richard

Brautigan. New York: Warner, 1972.

"Old Lady." The San Francisco Poets.

Ed. David Meltzer. New York: Ballantine Books, 1971. 293-97,

304.

Wright, Lawrence.

"The Life and Death of Richard Brautigan." Rolling Stone

Apr. 1985: 29-61.

Richard

Brautigan: An Annotated Bibliography

John F. Barber

|